A Practical Guide to BLE Throughput

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) was first added to smartphones in 2011 as part of the iPhone 4S. Since then it has become the de-facto way for smartphones to communicate with external devices. While BLE was initially intended to send small amounts of information back and forth, today many applications stream large amounts of data, such as sensor data for tracking steps, binaries for firmware updates, and even audio. For these types of applications, the speed of transfer is very important.

In this article, we dive into the factors which influence BLE throughput. We will walk through the BLE protocol stack from version 4.0 to 5.1. We will discuss how to audit what is limiting throughput in a BLE connection and parameters which can be tuned to improve it. Finally, we will walk through a couple practical examples where we evaluate and optimize the throughput of a connection.

I recommend starting with our Primer on Bluetooth Low Energy if this is your first time working with BLE.

Table of Contents

Bluetooth Low Energy Packet Structure

To best understand how to optimize for BLE, it’s first important to have a basic understanding of how the lower layers of the stack work together.

Terminology

Before we get started, there are a couple pieces of terminology that we will use extensively below:

-

Connection Event - For BLE, exactly two devices are talking with each other in one connection. Even if data is not being exchanged, the devices must exchange a packet periodically to ensure the connection is still alive. The start of every period in which two devices can exchange information with one another is known as a Connection Event. A connection itself is thus a sequence of Connection Events.

-

Connection Interval - The time between each Connection Event. The Connection Interval can be negotiated once the two devices are connected. Longer connection intervals save power at the cost of latency. Connection Intervals can range from 7.5ms to 4s.

Bluetooth Baseband / Radio

For Bluetooth 4.0, the BLE Radio is capable of transmitting 1 symbol per microsecond and one bit of data can be encoded in each symbol. This gives a raw radio bitrate of 1 Megabit per second (Mbps). This is not the throughput which will be observed for several reasons:

- There is a mandatory 150μs delay that must be between each packet sent. This is known as the Inter Frame Space (T_IFS).

- The BLE Link Layer protocol is reliable meaning every packet of data sent from one side must be acknowledged (ACK’d) by the other. The size of an ACK packet is 80bits and thus takes 80μs to transmit.

- The BLE protocol has overhead for every data payload which is sent so some time is spent sending headers, etc for data payloads

Fun Fact: As an antenna is used it heats up. As it heats up, the frequency it transmits or receives at can start to drift. The IFS allows for simpler antenna design & stabilization circuitry for BLE by giving the antenna a chance to cool down before it needs to transmit or receive again, which helps to keep chip costs down.

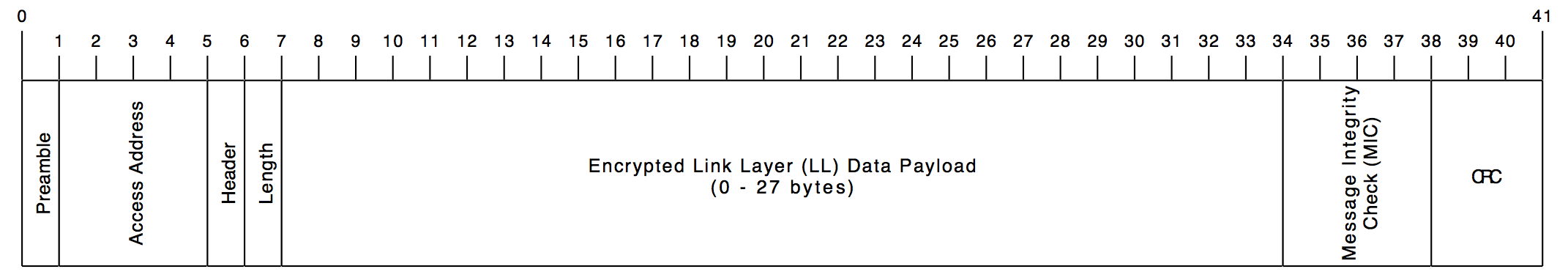

The Link Layer (LL) Packet

All data during a BLE connection is sent via Link Layer (LL) packets. All higher level messages are packed within Data Payloads of LL Packets. Below is what a LL Packet sending data looks like (each tick mark represents 1 byte):

NOTE: The astute reader may note that Data Payload can be up to 251 bytes. This however is an optional feature known as “LE Data Packet Length Extension” which we will explore in more detail below

Maximum Link Layer Data Payload Throughput

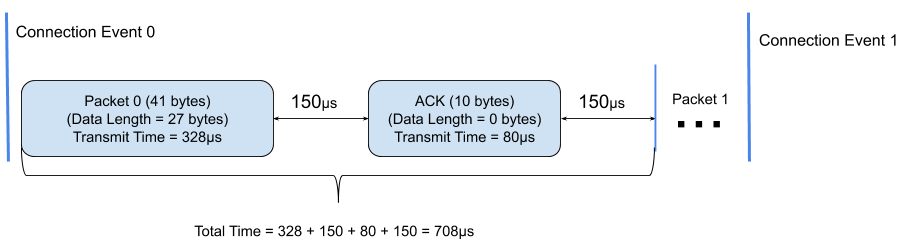

With the three rules we mentioned about transmissions on the Bluetooth Radio in mind, let’s take a look at the procedure to transmit a maximally sized LL packet.

- Side A sends a maximum size LL data packet (27 bytes of data in a 41 byte payload) which takes 328μs (

41 bytes * 8 bits / byte * 1Mbps) to transmit - Side B receives the packet and waits

T_IFS(150μs) - Side B ACKs the LL packet it received in 80μs (0 bytes of data)

- Side A waits

T_IFSbefore sending any more data

Here’s an example exchange of two packets of data in one Connection Event:

The time it takes to transmit one packet can be computed as:

328μs data packet + 150μs T_IFS + 80μs ACK + 150μs T_IFS = 708μs

During this time period, 27 bytes of actual data can be transmitted which takes 216μs.

This yields a raw data throughput of:

(216μs / 708μs) * 1Mbps = 305,084 bits/second = ~0.381 Mbps

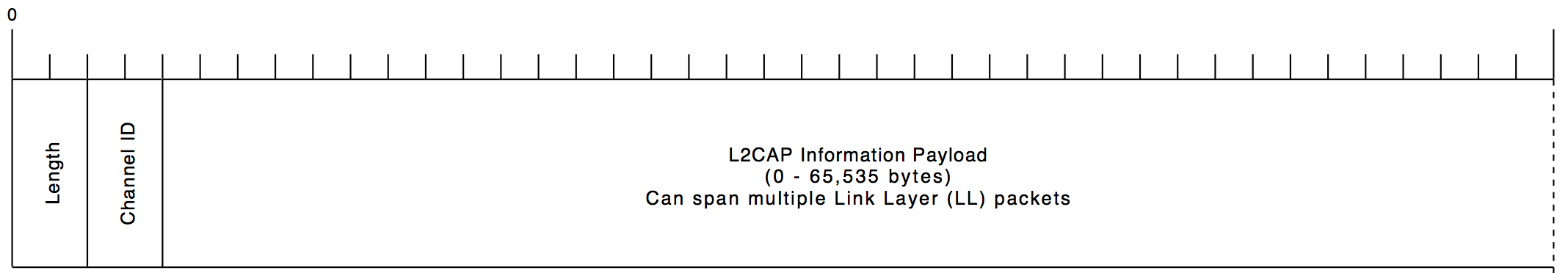

L2CAP Channels & Payloads

L2CAP is the next layer above the Link Layer and is packed inside the Data Payloads of the Link Layer packets. L2CAP allows:

- unrelated data flows to be multiplexed across different logical channels

- fragmenting and de-fragmenting data across multiple LL Packets (since an L2CAP payload can span multiple LL Packets)

There are only a few different L2CAP channels used for Bluetooth Low Energy:

- Security Manager protocol (SMP) - for BLE security setup

- Attribute protocol (ATT) - Android & iOS both offer APIs that allow 3rd party apps to control transfers over this channel.

- LE L2CAP Connection Oriented Channels (CoC) - Custom channels which are advantageous for streaming applications. Apple exposed APIs for L2CAP Channels in iOS 111. Android also exposed APIs as part of Android 102. Since both of the mobile APIs are still fairly “new” and many phones aren’t running OS updates which support these features, most devices which need to talk to a mobile device still need to use ATT. If your application does not need to send data to a mobile device, it’s definitely worth trying to use CoCs!

The L2CAP Packet

Below is a diagram of the layout of an L2CAP packet. As you can see there are 4 bytes of overhead (Length + Channel ID) per packet sent.

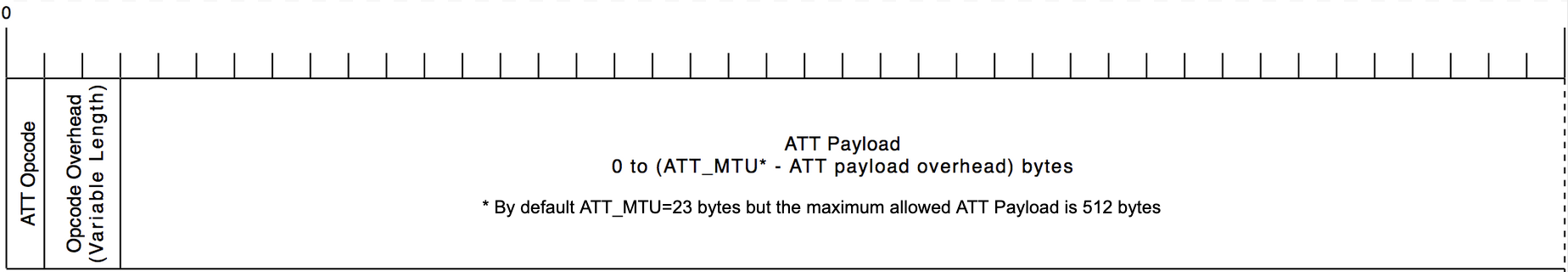

Attribute Protocol (ATT) Packet

In the L2CAP Information Payload we have the ATT packet. This is the packet structure the GATT protocol uses.

NOTE: For an excellent article about GATT itself, check out Mohammad Afaneh’s thorough BLE Primer post on the topic!

ATT packets can span multiple LL packets. The size of the data unit within an ATT packet is known as the Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU). The default size is 23 bytes (which allows the packet to fit in one LL packet) but the size can be negotiated via the Exchange MTU Request & Response.

Per the Bluetooth Core Specification, the maximum allowed length of an attribute value (the ATT payload) is 512 bytes3. While this technically means the MTU size can be slightly larger than 512 bytes (to accomodate for the ATT protocol overhead), most bluetooth stacks support a maximum MTU value of 512 bytes.

The packet looks like this:

Maximum throughput over GATT

The Attribute Protocol Handle Value Notification is the best way for a server to stream data to a client when using GATT. The Opcode Overhead for this operation is 2 bytes. That means there are 3 bytes of ATT packet overhead and 4 bytes of L2CAP overhead for each ATT payload. We can determine the max ATT throughput by taking the maximum raw Link Layer throughput and multiplying it by the efficiency of the ATT packet:

ATT Throughput = LL throughput * ((MTU Size - ATT Overhead) / (L2CAP overhead + MTU Size))

Tabulating this information for a couple common MTU sizes we get:

| MTU size (bytes) | Throughput (Mbps) |

|---|---|

| 23 (default) | 0.226 |

| 185 (iOS 10 max) | 0.294 |

| 512 | 0.301 |

Bluetooth Low Energy Specification Updates Impacting Throughput

Over the years, the Bluetooth SIG has added a number of additions to the Low Energy Specification to help improve the throughput that can be achieved. In this section we explore these settings.

CAUTION: Even though some of these features have been around for a while, support within the ecosystem still varies. If you are planning to leverage these features, I’d strongly recommend having away to dynamically enable/disable them in your software stack. While the Bluetooth Specification has a robust set of hardware level BLE “Direct Test”s a device must pass to be certified, there really is no thorough test of the software stack itself. This in part has contributed to very buggy BLE software stacks getting shipped and numerous interoperability issues when different Bluetooth Chips try to talk to one another.

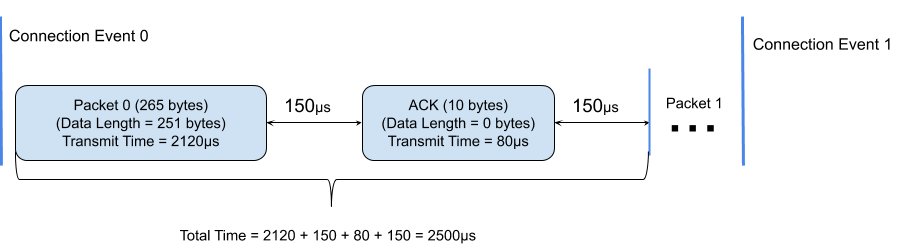

LE Data Packet Length Extension (BT v4.2)

As part of the 4.2 Bluetooth Core Specification revision, a new feature known as LE Data Packet Length Extension was added 4. This optional feature allows for a device to extend the length of the Data Payload in a Link Layer packet from 27 up to 251 bytes! This means that instead of sending 27 bytes of data in a 41 byte payload, 251 bytes of data can now be sent in a 265 byte payload. Furthermore, we can send a lot more data with fewer T_IFS gaps. Let’s take a look at what exchanging a maximally sized packet looks like:

We can calculate the raw data throughput and see that this modification yields greater than a 2x improvement on the maximum raw data throughput which can be achieved!

251 bytes / 2500μs = 100.4 kBytes/sec = ~0.803 Mbps

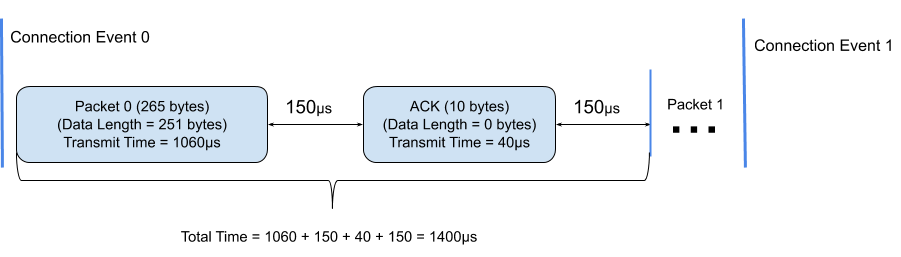

LE 2M PHY (BT v5.0)

As part of the 5.0 Bluetooth Core Specification revision, a new feature known as “LE 2M PHY”5 was added. As you may recall in the section above, we discussed how the BLE Radio is capable of transmitting 1 symbol per μs for a bitrate of 1Mbps. This revision to the Bluetooth Low Energy Physical Layer (PHY), allows for a symbol rate of 2Mbps. This means we can transmit each individual bit in half the time. However, the 150μs IFS is still needed between transmissions. Let’s take a look on how this impacts the throughput when sending packets that are using the data packet length extension feature:

We can calculate this throughput and see the modification yields almost a 4x improvement over the original maximal raw data speed that could be achived with BLE 4.0:

251 bytes / 1400μs = 179.3 kBytes/sec = ~1.434 Mbps

LE Coded PHY (BT v5.0)

The “LE Coded PHY” feature, also introduced in the 5.0 Spec 5 provides a way to extend the range of BLE at the cost of speed. The feature works by encoding a bit across multiple symbols on the radio. This makes the bits being transmitted more resilient to noise. There are two operation modes where either two symbols or eight symbols can be used to encode a single bit. This effectively reduces the radio bitrate to 500 kbps or 125kbps, respectively.

Auditing BLE Throughput Limiting Factors

LE Protocol Analyzers

A full discussion of how to use protocol analyzers is outside the scope of this article but they can be an invaluable resource when trying to understand performance issues on your Bluetooth link. They give you detailed views of the raw packets being sent over the air and very useful visualizations of the data being sent at the different protocol layers.

My two favorite analyzers on the market today are the

Both of these are built on top of a Software Defined Radio (SDR) meaning as the BLE spec evolves, the vendors should be able to ship a software update adding the support rather than requiring you purchase new hardware. Both these analyzers already support new features that have been added as part of BLE Specification revisions (Data Packet Length Extension, Channel Selection Algorithm #2, LE 2M & Coded PHY) which are becoming must have features when analyzing communications between the latest BLE chips. The Ellysis analyzer will also let you feed external GPIO lines into the analyzer that you can see synchronized with your transmissions sent over the air, which can be super helpful for debugging classes of bugs related to RF transmit windows.

Note: /u/introiboad on Reddit8 also pointed out that the Nordic BLE Sniffer9 can be a great tool for tracing connections and is a fraction of the cost because all you need to use it is a nRF52 development board.

Throughput Optimization Checklist

Ultimately, there are a number of variables that influence the throughput achieved during a BLE connection. Furthermore, there’s several parameters that can vary widely depending on the software stack of the bluetooth chip in use and have a significant impact on throughput. In the sections below, I’ll discuss the common settings to check when trying to analyze and optimize the throughput of a connection.

NOTE: If you are evaluating a Bluetooth chip for a new design, it’s very important you are using a capable chip to test the new one against. If you are testing the new chip against one with the limitations described below, you may miss some of the limitations of the new chip being analyzed.

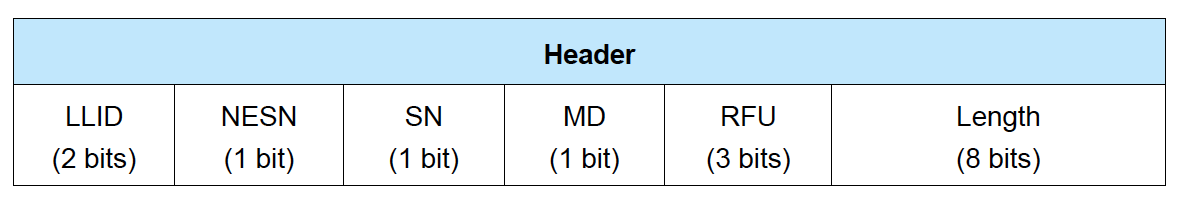

Supported Packets Per Connection Event

The number of packets which can be transmitted in one connection event is limited by the Bluetooth software stack in use. Some older devices only support one packet per connection interval. Assuming the fastest connection interval, 7.5ms, this would mean the max raw data throughput which could be realized is only:

27 bytes / 7.5ms = 3.6kBytes / second = 0.029 Mbps

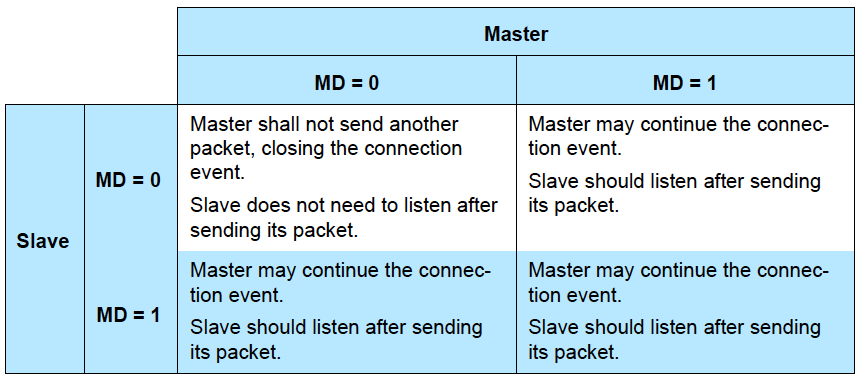

The end of a connection event is controlled by the More Data (MD) bit in the header of the link layer packet discussed above. The LL packet header looks like this:

A good description of how the MD bit works can be found in the Bluetooth Core Specification 5

If you have a protocol analyzer, you can analyze how the MD is being set to figure out what side of the connection is responsible for limiting the throughput.

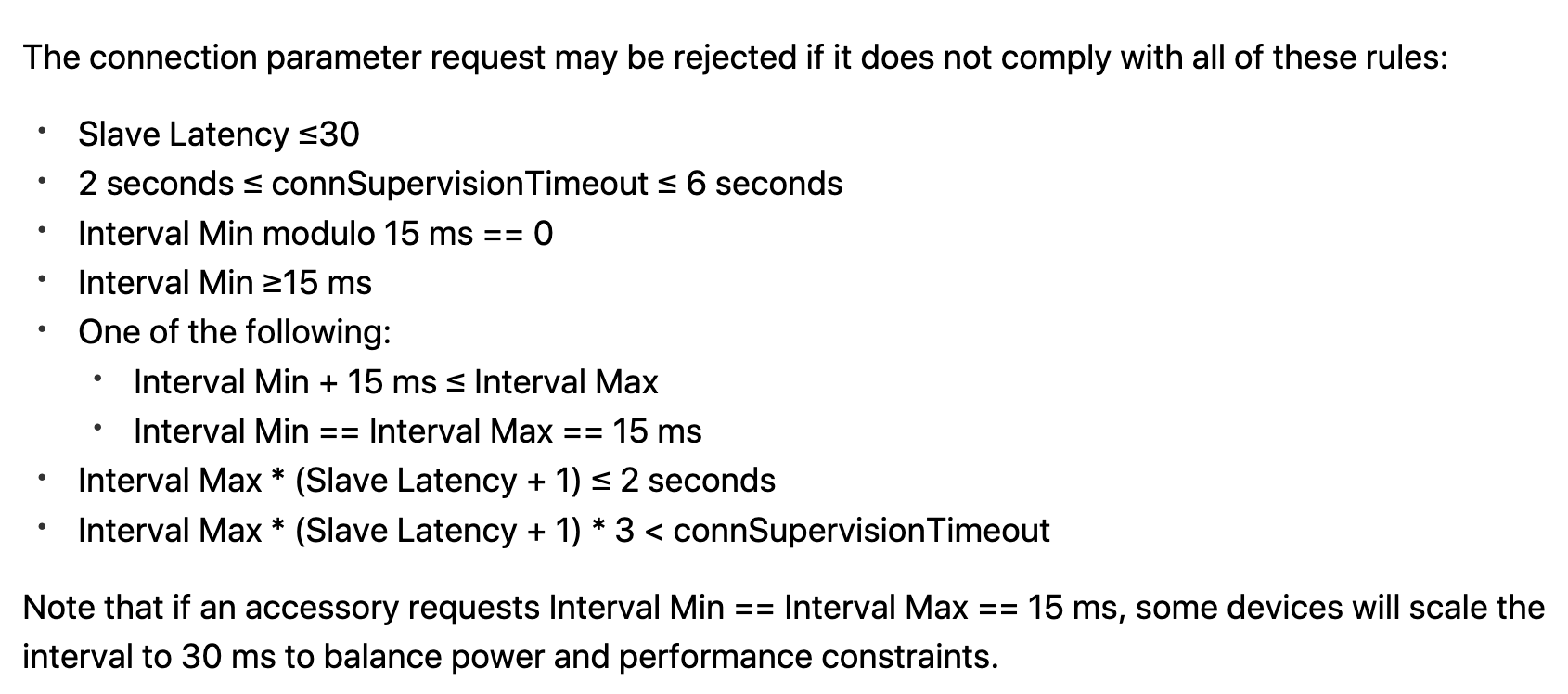

Supported Connection Intervals

Many devices only support a subset of the valid connection parameter range (7.5ms - 4s). For example, Apple documents this information quite well in Section “25.6 Connection Parameters” of the “Accessory Design Guidelines For Apple Devices” 10:

A longer connection event in itself isn’t necessarily a problem for throughput. Some devices will send and recieve data for an entire connection event so if you are streaming data continuously the same throughput can be realized even if you are using a 30ms interval instead of a 15ms interval.

What the connection interval does impact is latency. Many higher layer protocols have messages which need to be acknowledged by higher level software components. The longer the connection interval, the longer it will take for these round trips to complete

Maximum Supported ATT MTU Size

As we discussed above, the ATT MTU size has an impact on the max throughput which can be realized when using GATT due to protocol overhead. Some chips only support the default size (especially older Android Phones). When first testing a chip it’s important to check and make sure larger packets can be sent! It’s also a good idea to see how many ATT packets you can queue up and receive. Some stacks will only let you queue up or receive a single MTU worth of data so it’s not possible to keep the link saturated.

Coexistence

A lot of devices share the 2.4GHz antenna for several different RF protocols. For example, on a phone this would typically be Bluetooth Classic (used for things like audio streaming to speakers), Bluetooth LE & WiFi. Additionally, sometimes for Bluetooth there will be multiple simultaneous connections that need to be managed.

When multiple devices are sharing the same radio, the software stack on the device will assign some prioritization between the different protocols. For example, the scheduler in a phones may prioritize traffic based on whether the app using the connection is in the foreground or background or streaming audio.

Reliability

Counterintuitively, even though the Link Layer of BLE is reliable, packet loss is still something to be concerned about for BLE. This is because many many stacks drop data within the software stack. For example, BLE messages get queued up in the stack and when the heap holding the packets runs out of memory, some stacks will silently drop data. This means if you are sending large amounts of data over BLE you will usually want to add some sort of reliability layer that can detect & retransmit messages when data is dropped. The way this is implemented can have sizeable impacts on throughput. For example, if you have designed your own protocol on top of L2CAP or GATT and every message sent requires an acknowledgement before another message is sent, you’ll typically wind up adding a connection interval worth of latency getting the data sent out, effectively halving the max throughput which can be achieved.

NOTE: If you are using GATT and trying to optimize throughput you will want to check the GATT operation types being used.11 From a Server to a Client, it is favorable to send Notifications instead of Indications because Indications require a round trip Confirmation to be sent before another message can be sent. From a Client to a Server you will want to use Write Commands instead of Write Requests because Requests require a Response from the Server. In general, I’d advise not relying on Indications or Requests if you need reliability because data can still be dropped on many stacks before making it to your application (especially on mobile).

Maximum Supported Link Layer Data Packet Size

As mentioned above, as of Bluetooth 4.2, the size of a Link Layer data payload can be up to 251 bytes. However, not all devices support this maximal size. Ideally, you’ll want to test the chip you are using and make sure it supports the entire range. For optimal throughput you’ll want to make sure the connection interval is an integer multiple of the packet transmission time. We will walk through an example of this below

Examples

iPhone SE BLE Throughput Analysis

For iOS 10 and above, most iOS devices support a 185 byte MTU and 7 packets per connection interval. The lowest connection interval which can be negotiated for normal applications is 15ms. Let’s take a look at the realistic throughput which can be achieved!

First let’s make sure we can transmit 7 packets in 15ms:

7 * (328μs Data + 150μs + 80μs ACK + 150μs) = 4.956ms

Now that we know the packets fit, we can take the duty cycle we are achieving and multiply it by the ATT throughput maximums tabulated above.

Data Rate = (4.956ms / 15ms) * 36.7 kBytes/Sec = 12.2 kBytes/sec = 0.10 Mbps

Optimizing throughput Example

Let’s figure out if we can improve the throughput for the following application:

- the connection parameter being used is 11.25ms (minimum supported for the device we are using)

- data packet length extension is being used with 251 byte packets being sent

- both devices will send as much data they can fit in a connection interval

- 1 MB PHY is being used

From the examples above, we know it takes 2500μs to exchange a 251 byte data payload. This means we can fit 4 transfers in a 11.25ms connection interval. No data will be sent in the last 1.25ms of the window since it does not fit. This gives us a throughput of:

(251 bytes * 4 packets) / 11.25 ms = 89kBytes/sec = 0.713Mbps

If we chose a slightly larger connection interval that is a multiple of our transfer duration (2500μs) we can fill the connection interval without any gap where no data is sent. For example, in a 12.5ms window, we can fit 5 packets perfectly. This gives us a ~13% improvement in overall throughput:

(251 bytes * 5 packets) / 12.5 ms = 100.4kBytes/sec = 0.803Mbps

The important takeaway here is that in some scenarios a slower connection interval can actually yield faster throughput!

Closing

I hope this post gave you a useful overview of the factors which control BLE throughput and how you could audit what is impacting the performance you are seeing and improve it!

Are there any other topics related to BLE throughput you’d like us to explore further? Are there any cool optimizations you have made in the BLE stack you use today? Let us know in the discussion area below!

See anything you'd like to change? Submit a pull request or open an issue on our GitHub

Further Reading

For iOS specifically, a few readers12 pointed out this slide deck and video from 2017 WWDC. The presentation provides an excellent overview of how to get the most out of iOS Core Bluetooth.

Reference Links

-

See “3.2.9 Long Attribute Values” of the Bluetooth 5.1 Core Specification ↩

-

See comment from /u/writtenabode on Reddit and oflannabhra on HN ↩